All tagged apartment

Causeway Gardens

“The more work I got, the cheaper I could build, because I could use standardisation and mass production and the more I built, the cheaper they got, and cheaper they got, the more I built, and this was a sort of vicious circle in reverse.” [1]

From the early years of the Swan River Colony, wetlands were used as convenient repositories for rubbish dumping.

In later years, municipal authorities gazetted wetlands as rubbish tip sites, and metropolitan rubbish was dumped into the wetlands until they were full. They were then flattened and used as sports grounds, parks and ovals.

Lake Poulett was drained in 1872, and after serving as the town rubbish dump and then Chinese gardens, was partly used for the formation of Birdwood Square in 1914 (Seddon 1972).

By 1901 the clay pits east of Plain Street had been transformed into Queens Gardens but directly across the road was the East Perth rubbish tip filled with water, overflowing with rubbish and surrounded by mud and decay, it was a standing disgrace. In 1904 the tip was covered with sand and transformed into sports playing fields which are now the Western Australian Cricket Association grounds (WACA) (Stannage 1979).

The Eastside Gardens in East Perth is the the first building in Australia to be constructed entirely from slipformed concrete. To achieve greater heights beyond the scope of brick construction, architects Krantz and Sheldon, commissioned by the Bond Corporation. developed a construction technique that was superior in the speed of construction which significantly saved costs. This new construction technique allowed Krantz and Sheldon to benefit in the economies of mass production.[2] For the first time in Perth, a building could be constructed at a high output of efficiency and speed. In this regard, bulk orders of building fittings and fixtures such as doors, windows, stoves, furnishings, locks and the like, were ordered at a high turnover and therefore at a cheaper rate. Krantz could design and construct buildings cheaper and quicker than anyone else in Perth, and was based on the ability for standardization in their buildings. Their desire to continue building flats at an ever increasing rate through methods of rationalized efficiency became the norm, taking this building as one of the first to what we see today in contemporary apartments.

Notes:

[1] Jane Fleming, “Krantz Interview”, 1981.

[2] Crist, Graham, “Krantz and Sheldon: Modernity and urbanism. Flats in Perth 1930-1980”, (Dissertation, University of Western Australia, 1990), 62.

Mount Street Flats

This example of apartment living bears a marker of change to domestic living that was at the time, just outside the CBD. Containing a combination of bachelor flats and two bedroom flats, this building comes from a direct influence from the European Modernist tradition by Robert Sheldon, soon to be partner of Harold Krantz. Sheldon, an immigrant himself brought with him a European experience of Modern urbanism, with a sophistication approach to construction that had a notable impact of shaping Perth city and its surrounding suburbs to come.

Walkups II

Further along Stirling highway, at numbers 72 and 74 are more domestically scaled maisonettes. The seemingly single masisonette has been carefully planned into four separate dwellings to each floor. Without conflicting with the planning restrictions, plot ratios or height restrictions, Krantz had allowed for a higher density of living within the predominate detracted cottage dwelling in the area.

Jubilee Street Townhouses

Over two decades after his first Mansard housing development, Jeffrey Howett adapts his hidden storey again here on Jubilee Street, (1975) now with black painted tiles. On this note, Michael Markham pointed out an in interesting dichotomy with Howett’s progressive adaption to the finish of the Mansard tiles. Where Onslow Street exhibited painted white tiles, a gaze towards Modernism’s purity, here, we discover the inverse effect, black. To mediate such an effect emerges into Postmodernism’s ideology.[1] Modernist discourse aside, these Mansard (and rather peculiar) projects conceived by Howlett, succeed in challenging both the relationship with scale and density in town housing and the notion behind, specifically, the typical mansard townhouse. By making ambiguous statements in the proportioning of the roof component, in turn, compositionally balances on the edge to be an either a sloping wall or a roof. What is also remarkable is that Howlett’s mansard buildings partake in a two-decade housing experiment concerned with the typology of housing,[2] and has led to many other imitators of its kind.

Another note to mention in Howlett’s mansard townhouses is in his preference to resist a townhouse to be a detached dwelling. Instead, he has favored the quasi-stretched manor type. As a consequence, as noted by Markham through his windscreen driving past these projects, they are hard to see that they are indeed broken internally with separate dwellings inside their extruded linear volume. Conveying a similar type to the terrace or row house these rather old Mansard projects are therefore quite unique for Perth’s preference for the detached dwelling.

Notes:

[1] Michael Markham, “John Glenn’s Skyline,” Jeffery Howlett, Architectural Projects, Lawrence Wilson Gallery, 1992.

[1] Markham, “John Glenn’s Skyline,” 1992.

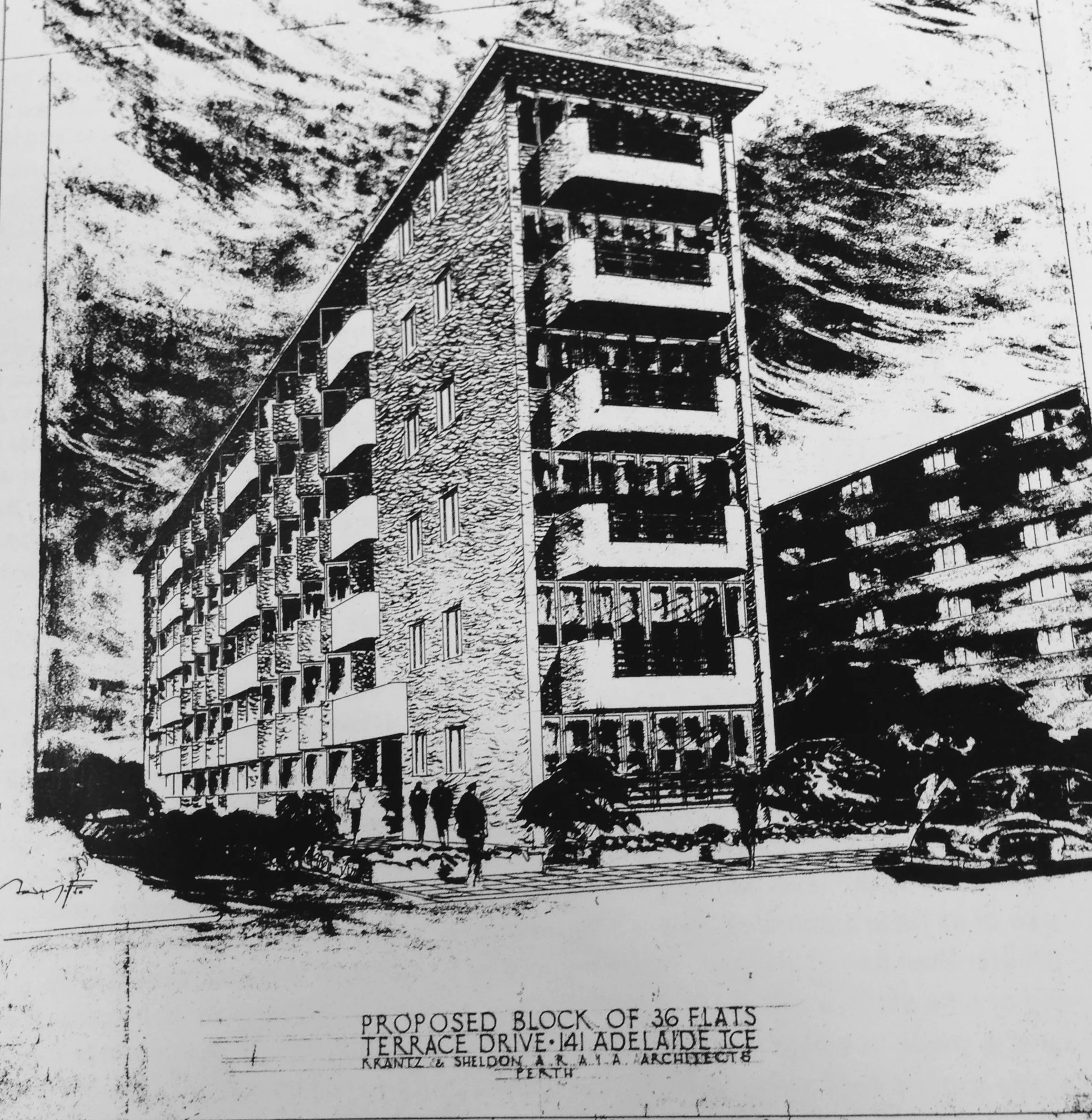

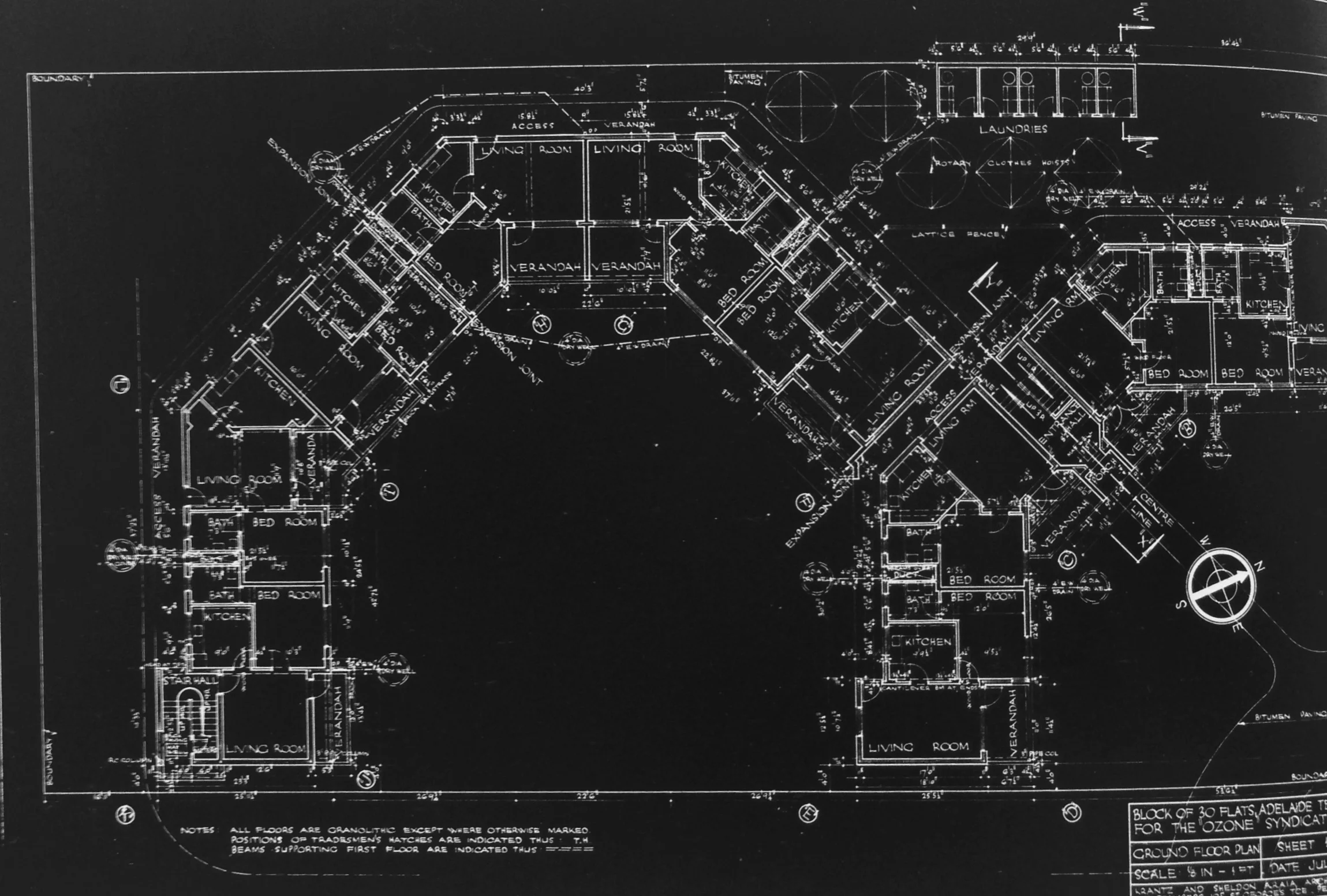

Terrace Road Walkups

The legendary architectural practice of Krantz and Sheldon has more than anyone else in Perth, has pushed the relevance and validity of flats as a modern housing type for urban life. Nearly all of these developments were procured from private interest and funded with syndicates with Krantz and Sheldon being both the client and developer.

Krantz and Sheldon’s walk up flats along Terrace Road in Perth bears no exemption here and demonstrate good examples of the walk up flat typology. Challenging the the city’s by-laws at the time, these walkup flats along Terrace Road were developed to the maximized allowable extent. Unlike developers today, Krantz and Sheldon sourced and purchased available land close to the city, found clients that were willing to be onboard in funding their developments by charging them the architectural fees and construction costs. A syndicate of a few people could get together, pool their funds and build something on the recently purchased land. In this regard, Krantz and Sheldon were, by todays standards, all at once the architect, developer, builder and client with the help of the syndicate. What’s more, their sustained ability to keep a high turnover included Krantz and Sheldon’s interest in investment into their own projects. By taking a couple units themselves to be used for investments for the following development enabled Krantz and Sheldon to continue this methodology. Not seeing any economical return in developing in the greater suburbs, Krantz and Sheldon’s success during this period were in their interest on the housing demand in the city. The major advantage being that they were able to achieve a higher density of housing units and therefore achieved a higher economical return.

Whist these apartments are by todays standards based may be conceived to be small and cheap in their aesthetic appearance, were constructed economically to a sophisticated level of practicality. By working within tight budgets whist focusing on a refined architectural detail to reduce the risk of building maintenance and roof leaks, these walk-ups by Krantz and Sheldon should be still merited for their endurance and sustainability based of evidence of good design in the city.

Herdsman Lake Hexagons

Another one of Krantz and Sheldon's housing experimentations through the act of building, the 'Hexagon' model can be found along the Herdsman Lakes, Wembley.

Under the very tight budget constraint, these tightly planned units led towards the goal to maximise efficiency and can still be found useful to the contemporary designer.

Image source: Graham Crist, RMIT.